|

By Mark Ward

BBC News website

|

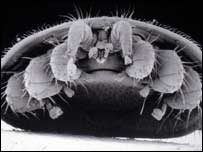

The varroa mite has devastated bee colonies all

over the

world |

The US

is in danger of running out of honey bees to pollinate its almond

crop - the country's number one horticultural export.

February and March are the crucial months for almond growers, as

this is when trees blossom and need pollinating.

At this time of year, owners of commercial hives take their

valuable cargos to California, where almost 80% of the world's

almonds are grown, to service the blossom.

Annually the crop is worth more than $2.5bn and a lot of jobs

depend on a good harvest, explains Dan Cummings, one of the

directors of California's Almond Board and head of its bee task

force.

Currently about 222,000 hectares are under production to grow

almonds. Mr Cummings expects this to grow to 330,000 hectares over

the next five years.

But, said Mr Cummings, that growth presented a real problem.

"Roughly two-thirds of the bees in the US need to come to

California for almond pollination," said Mr Cummings. "Beekeeping in

the US is very much migratory."

Hive mind

The danger is that as the demands of almond growers for healthy

hives grow, America will simply not have enough commercial colonies

available to travel. Bees travel from as far away as North Carolina

to California just so they can be used at the key pollination

season.

"Last year we were a little short," said Mr Cummings.

Already, he said, demand for colonies was driving up the price

that beekeepers charged for renting out their colonies.

Mites stunt bee growth and make them vulnerable

to disease |

In

2004, beekeepers could get, on average, $54 for every hive they sent

to almond groves in California. Last year, prices peaked at about

$85, and in 2006 there are reports of owners charging more than

$150.

To make matters worse, American bees are suffering a resurgence

of debilitating attacks from the varroa mite. These tiny parasites

stunt the growth of bees, sap hive resources and slowly kill off the

colony.

Unfortunately, said Mr Cummings, bee colonies badly affected by

varroa typically collapsed at about the same time as almond trees

came into flower.

While chemical treatments can help manage the problem, many

pesticides have been so widely used that some mites have developed

resistance.

Finding a better way to manage mites had become a pressing

problem, said Mr Cummings, because of the tight relationship between

the health of beehives and the size of the almond crop.

Chemical control

American beekeepers are now turning to a British development to

help them tackle resistant varroa mites.

Developed by Vita Europe, the thymol-based treatment is derived

from thyme, and vapours from oil extracted from the herb have proved

useful in killing the varroa mites.

Dr Max Watkins, technical director of Vita Europe, said: "Thymol

works in a very different way from traditional pesticides which

target specific points on the nervous system."

By contrast, he said, thymol has a much wider effect on varroa

physiology.

In tests, thymol had been able to knock out more than 90% of the

mites in a colony, said Dr Watkins.

"It's a little more difficult in theory for something to become

resistant to that," he added.

Dr Watkins explained that thymol tended to knock out both

resistant and non-resistant varroa mites, so beekeepers could use it

in rotation with established treatments to keep the numbers of

parasites under control.

Vita's anti-varroa treatment is now undergoing certification in

the US.

Although certification will come too late for the 2006 almond

pollinating season, Dr Watkins expects it to be in wide use to

prepare bees for the 2007 crop.